“The deep sea, with vast expanses of water and seabed, between 200 and 11,000 metres below the ocean’s surface, is recognised globally as an important frontier of science and discovery,” points out marine biologist Ana Hilário, coordinator of the Challenger150 programme alongside Kerry Howell, a researcher at the University of Plymouth (UK) and specialist in Deep Sea Ecology.

Ana Hilário, researcher at the Centre for Environmental and Sea Studies (CESAM) of the University of Aveiro (UA), notes that “although the deep sea represents about 60 percent of the Earth’s surface, a large part remains unexplored and humanity knows very little about its habitats and how they contribute to the health of the whole planet”.

To unlock these ‘secrets’, Ana Hilário and Kerry Howell have assembled a team of scientists from 45 institutions in 17 countries to work for a decade on the study of the deep sea.

From Portugal, besides the UA, scientists from the Interdisciplinary Centre for Marine and Environmental Research (CIIMAR) of the University of Porto, the Okeanos Research and Development Centre of the University of the Azores and the Centre for Marine and Environmental Research (CIMA) of the University of Algarve also contributed to the design of the programme.

CIMA 20 Years Promoting Science

Asked by Lusa whether deep sea research can open the door to the depletion of more natural resources, the researcher admits that it can, but stresses that the objective is “to know more in order to use it better”.

“We cannot limit knowledge with the premise that we will destroy”, she adds, stressing that the premise has to be “better use”.

Ana Hilário told Lusa that “there is a lot of evidence of the potential” of the deep sea and that it is necessary “to acquire enough knowledge to decide whether it is worth exploring by providing information to policy makers.

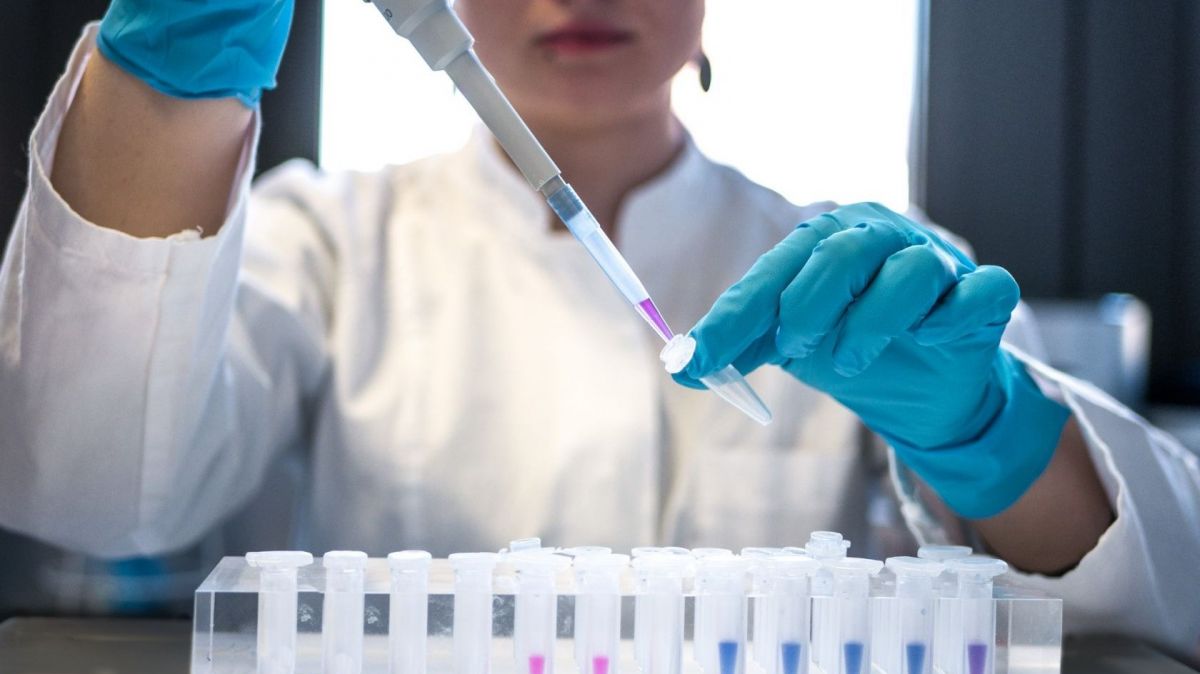

According to the scientist, in addition to the mineral potential, there is enormous potential in terms of blue biotechnology, with the possibility of obtaining new drugs and new chemical compounds, “with millions of applications”.

“One of the possible treatments related to Covid-19 comes from a new compound that has been discovered in a deep, sea organism”, she exemplifies.

Ana Hilário believes that “there is immense potential for the discovery of new chemical compounds with applications in all areas, from pharmaceuticals to cosmetics and science”.

“One of the molecules most used today in all the laboratories that do work in genetics comes from a bacterium that was discovered in the deep ocean”, she comments.

Even in the fishing industry “which is increasingly being done at greater depths, this does not invalidate the search for a better knowledge of the system, even to know how to preserve it”.

Challenger150, scientists hope, will generate more geological, physical, biogeochemical and biological data through innovation and the application of new technologies, and use that data to understand how changes in the deep sea affect the entire marine environment.

This new knowledge will be used to support regional, national and international decision making on issues such as deep sea mining, fisheries and biodiversity conservation, as well as climate policy.

“Our vision is that within 10 years, any decision that could have an impact on the deep sea in any way will be taken on the basis of sound scientific knowledge of the oceans,” says Kerry Howell, quoted in a statement from the University of Plymouth.

For this to be achieved, the British researcher stresses, “there needs to be consensus and international collaboration”.

The programme’s researchers publish a call, on 25 November, for international cooperation in Nature Ecology and Evolution magazine, while at the same time publishing a detailed outline of Challenger150 in Frontiers in Marine Science magazine.