The twenty-year Afghan war was never more than

discordant noises off-stage for most people in the rich Western countries that

sent troops there, so you can’t expect them to remember the ‘lessons’ of that

war. The Afghans never had any real choices in the matter, so they have no

lessons to remember. But Western military and political elites should do

better.

The first lesson is: if you must invade somebody, do try to pick the

right country. Americans definitely wanted to invade somewhere and punish it

after the terrorist outrage of the 9/11 attacks, but it’s unlikely that

Afghanistan’s Taliban rulers were aware of Osama bin Laden’s plans. The

‘need-to-know’ principle suggests that they were not.

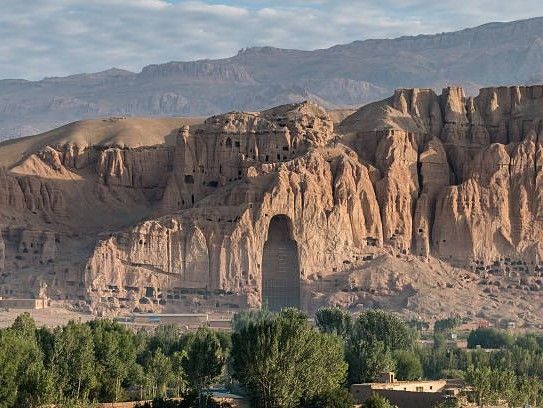

The second lesson is: whatever the provocation, never invade Afghanistan. It’s

very easy to conquer it, but almost impossible for foreigners to sustain a

long-term military occupation. Puppet governments don’t survive either. Afghans

have expelled the British empire at its height, the Soviet Union at its most

powerful, and the United States.

Terrorism is a technique, not an ideology or a country. Sinn Fein in early

20th-century Ireland had the same goal as Kenya’s Mau Mau rebels of the 1960s –

to expel the British empire – whereas the Western ‘anarchists’ of the early

1900s had no territorial base and (deeply unrealistic) global ambitions. So do

the Islamists of al-Qaeda today.

There are as many different flavours of terrorism as there are varieties of

French cheese, and each has to be addressed by strategies that match its

specific style and goals. Moreover, the armies of the great powers must always

remember the paramount principle that nationalism (also known as ‘tribalism’)

is the greatest force-multiplier.

Western armies got chased out of Afghanistan a year ago because they forgot all

the lessons they had learned from a dozen lost counter-insurgency wars in

former colonies between 1954 and 1975: France in Algeria and Indochina, Britain

in Kenya, Cyprus and Aden, Portugal in Angola and Mozambique, and the United

States in Vietnam.

The driving force in all those late-imperial wars was nationalism, and Western

armies really did learn the lesson of their defeats. By the 1970s Western

military staff colleges were teaching their future commanders that Western

armies always lose guerilla wars in the ‘Third World’ (as it was still known at

the time).

The Western armies lose no matter how big and well-equipped they are because

the insurgents are fighting on home ground. They can’t quit and go home because

they already are home. Your side can always quit and go home, and sooner or

later your own public will demand that they do. So you are bound to lose

eventually, even if you win all the battles.

But losing doesn’t really matter, because the insurgents are always first and

foremost nationalists. They may have picked up bits of some grand ideology that

let them feel that ‘history’ is on their side – Marxism or Islamism or whatever

– but all they really want is for you to go home so they can run their own

show. So go. They won’t actually follow you home.

This is not just a lesson on how to exit futile post-colonial wars; it is a

formula for avoiding unwinnable and therefore pointless wars in the ‘Third

World’. If you have a terrorist problem, find some other way of dealing with

it. Don’t invade. Even the Russians learned that lesson after their defeat in

Afghanistan in the 1980s.

But military generations are short: a typical military career is only 25 years,

so by 2001 few people in the Western military remembered the lesson. Their

successors had to start learning it again the hard way in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Maybe by now they have, but they’ll be gone too before long.

This cycle of learning and forgetting again doesn’t only apply to

pseudo-imperial wars in the post-colonial parts of the world. The wars between

the great powers themselves were having such frightful consequences by the time

of the First and Second World Wars that similar disasters have been deterred

for more than 75 years, but that time may be ending.

Like many other people, I oscillate between hope and despair in my view on the

course that history is taking now: optimistic on Mondays, Wednesdays and

Fridays, pessimistic on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, and I refuse to

think about it at all on Sundays.

Today is a [fill in the blank], and so I’m feeling [hopeful/despairing].

Gwynne Dyer is an independent journalist whose articles are published in 45 countries.