So it was when we went near Lousada for lunch, dodging wintry showers. It was as if we had stepped into a Hogarth painting, perhaps an eating house just off Gin Lane.

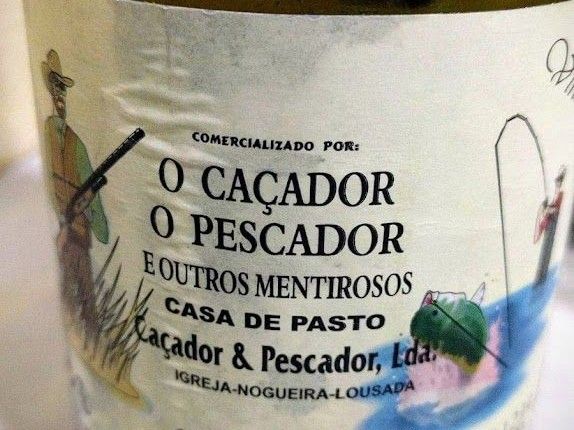

We should have known from the name: O Cacador O Pescador e outros Mentirosos (the hunter, the fisher and other liars) that this would be a little out of the ordinary. Obviously, we had chosen it for its outrageous name. The fact that the restaurant car park was full of mourners attending a wake in the Chapel of Rest next door added to the surreal nature of the occasion, the roar of Hogarthian jollity coming from one door and red-eyed weeping from the next.

Inside, it was as if we had stumbled upon a party that had been going full pelt for some time. Not a party fuelled overly by alcohol but by a kind of frenzied bonhomie. The place was doing a roaring trade in take-outs and this queue mingled with people waiting for a table. When I say 'queue' I obviously mean a haphazard jumble of bodies. Quite how anyone knew who might be next in line for either take-away or sit-down was a mystery but it did seem to work. Luckily, we had booked. The restaurant turned out to be a series of small rooms and we were found a table in the small room closest to the kitchen, where the real mayhem was concentrated. To say it was packed is to understate the effect. It was almost as if twice as many people were sitting at tables than chairs provided. They weren’t, of course. It just felt like it. Luckily, no one came to sit on my lap. No, really. I was squeezed up against the edge of the table as it was.

Signature dish

Our waiter was an insanely cheerful woman with the energy of half a dozen people. She was delighted to find that it was our first visit and declared without any fear of contradiction that we must have the nacos de vitela, their signature dish. It’s not that we would have chosen anything different, it’s just that, in the end, we weren’t given the choice. She swirled off with an infectious, throaty laugh. A few minutes later she came back to our table with a metal bowl from which she pulled a huge chunk of raw, bloody meat. Will this do you? We gulp. A moment of panic. We didn’t realise we had to eat it raw. Ah! We don’t. Sigh of relief. We nod our approval, though we assume we will be sharing the hunk of beef with another table, perhaps that one over there with a dozen people on it. No. Not at all. It’s all for us. Gales of laughter. She swishes off again, towards the kitchen, the half cow still in her hand, blood dripping from her fingers so that it can be thrown onto glowing charcoal.

It arrived back at the table after not very much time, or perhaps we simply hadn’t noticed time passing among all the excitement that our fellow lunchees obviously got from simply being there. The noise level was quite intense not just because of the sheer number of people but also because of the low ceiling. It hummed and throbbed, as if the building itself was alive. The meat had been cut into four smaller pieces and any one of them would have fed the two of us with enough left over in a doggy bag to get us through to Wednesday. Our waiter, had used both hands to carry the platter of meat - and she looked like she could hold up the back of a tractor with one hand and change the wheel with the other. You’ll need some potatoes and rice, she tells us. We don’t, but they come anyway. There are enough potatoes to fill a small field and enough rice to feed an entire village. She brings some extra bread as well, and we regretted having emptied one basket of it already. We make a start and gingerly cut a slice of the naco and try it. It is good. Very good. In fact, it is superb. We start to feel the madness shared by everyone else creep into us. The waiter comes by again and nods her approval. She can see in our eyes that we have been infected. She gives her full-throated laugh again. A celebration.

Afterwards – having declined half-hearted attempts to get us to choose a sobremesa – we go to look for a suitable incline up which to stride in an attempt to burn off some calories. Along the road, there is a pretty little chapel with a three-bell campanile and opposite a rather solar half hidden in a secret garden and with a beautiful carved veranda around the first floor. Next to the chapel the road strides smartly up a significant incline so we take it for a while, needing the incline, the chapel and lovely house to bring us back to a world we belong in. Our stomachs will take a while longer to recover. Then the rain started again - great icy shocks that soon quickened in pace and left us scurrying for the car.

Fitch is a retired teacher trainer and academic writer who has lived in northern Portugal for over 30 years. Author of 'Rice & Chips', irreverent glimpses into Portugal, and other books.

Pure delight to read your article! You're a talented, entrancing writer with such vivid descriptions that we are easily transported to one of the tables and the enthusiasm of the restaurant rings in our ears.

By Susan from Lisbon on 21 Feb 2024, 11:04